Memories - Narratives - Expectations

Today, hundreds of thousands of recorded interviews with contemporary witnesses are extant. The narratives differ from each other even though they are often similar. The testimonies are colored by the speakers’ experiences and observe no chronology. They are, in fact, remembered fragments strung together by association, which as a story keep defying any logic since they sometimes follow a storyline only to be suddenly pierced by unexpected emotional moments or augmented by new secondary knowledge.

The exhibition takes a look into the video collection of contemporary testimonies held by the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial. By way of example, it demonstrates how the events, the memory of National Socialism, its crimes as well as the history leading up to it and its aftermath have found their diverse narrative expressions.

"Intervals", Hana Malka (2009), running time: 3:02 min

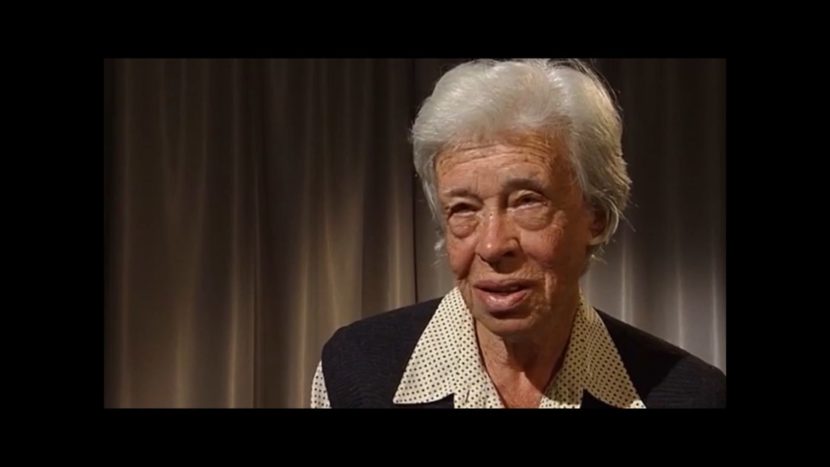

Whether and when someone decides to tell their story depends both on individual factors as well as on societal conditions. Those survivors who are still able to report today were children or youngsters at the time of war. Oftentimes, they start talking only after reaching retirement age. Hence, their stories are marked by their life experience and frequently entail a mandate for future generations.

Hana Malka refrains from talking about her experiences for decades. Even her children know very little. In her narrative, she reflects in a matter-of-fact manner on her long silence and the reasons for breaking it toward the end of her life. As contemporary witness, she wants to recount how things were. In particular, she addresses young people to enable them to carry on her legacy and resist developments early on that might lead to crimes against humanity.

"Distress", Shelomo Selinger (2015), running time 2:36 min

On both sides of the camera, interests and priorities exist as to content that ought to be addressed. Inevitably, this gives rise to tensions regarding room accorded to the survivors for their chosen topics. Then again, the witnesses, too, want to decide for themselves on what they consider worth telling within the given time, and how much room they need for their account.

Shelomo Selinger's wife calls an episode to his attention she considers worth talking about toward the end of the interview. His seven-year-long amnesia is a defining event in his life. Nevertheless, the interviewer, for lack of time, wants to limit this topic to a few sentences. After meeting his wife’s wish, Selinger manages to retrieve his original narrative thread.

"Key Moments", Charles Dekeyser (2007), running time: 1:17 min

Particularly those events become narrated memory that have special personal meaning for the narrators and occasionally shape their future life. For survivors, these are mostly moments when they themselves or persons close to them are threatened with terror and death. Often, such traumatic experiences bring about the rejection of habitual attitudes and perspectives.

Charles Dekeyser tells, deeply moved, that he had to watch how his friend was hanged at the roll-call square. Helplessly at the mercy of the SS, he asks in this moment God to save his friend. In the wake of this arbitrary act of terror and loss of a trusted person, Dekeyser loses his faith in religion.