Alfred Seltmann

January 9, 1899 – January 4, 1945

![]()

Alfred Seltmann, 1928, detail (Historical Archive of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Selters)

Loyal to his Faith

Alfred Seltmann was born in Irchwitz near Greiz. The trained machinist lived with his family in the town of Auerbach in the German Vogtland region. In late 1935, he was taken into protective custody as a Jehovah’s Witness and transferred to the Sachsenburg concentration camp. Half a year later, the Freiburg Special Court sentenced Alfred Seltmann to a jail term of six months for a violation of the Law Against Malicious Attacks. On December 12, 1936, Jehovah’s Witnesses staged demonstrations across Germany protesting their persecution by the regime. During these protests, Alfred Seltmann distributed fliers in Plauen. Soon thereafter, Alfred Seltmann was rearrested and sentenced to a jail term of three years. He served his sentence in the Bautzen penitentiary, in Zweibrücken, and in the Emsland camps of Neu-Sustrum and Meppen before being returned to the Plauen jail in January 1940.

Alfred Seltmann and his wife Ella with their four children, 1928 (Historical Archive of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Selters)

After Alfred Seltmann’s arrest, the Gestapo demanded that he renounce his faith. Alfred Seltmann refused, and was transferred to the Flossenbürg concentration camp on April 28, 1940. There he was put to work in the prisoners’ kitchen and in the gardens of the SS housing settlement. Alfred Seltmann died on January 4, 1945, with the cause of death officially listed as a heart condition.

After the war, the town of Auerbach renamed several streets after victims of fascism, including a street named after Alfred Seltmann. Even though the Jehovah’s Witnesses were banned in the German Democratic Republic, the street name was kept unchanged.

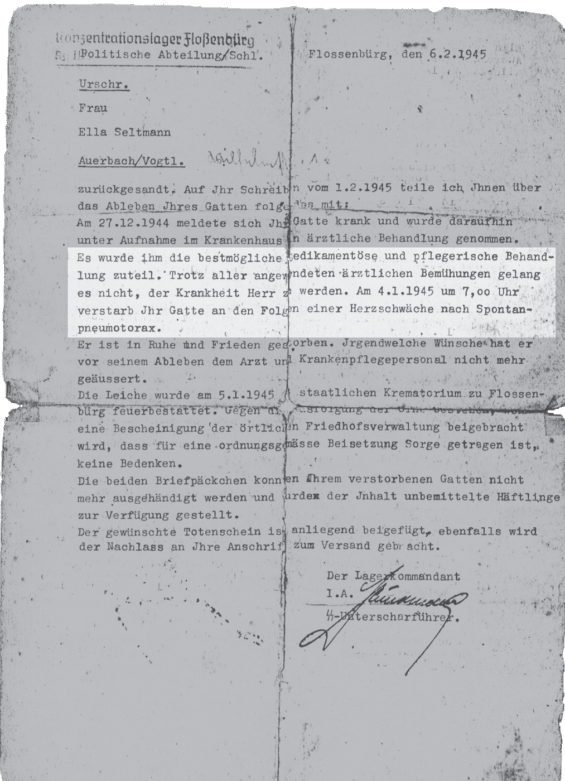

Letter from the Flossenbürg headquarters to the widow Ella Seltmann, February 6, 1945 (Historical Archive of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Selters)

This letter was sent to Ella Seltmann after she inquired about the local police notification of her husband’s death. As in all such letters, the camp headquarters attempted to maintain the appearance that prisoners were being treated properly.