Flossenbürg – Site of Granite (before 1938)

Before the establishment of the concentration camp, Flossenbürg was merely a small village in the Upper Palatinate forest. Beginning in the late 19th century, a number of quarries were opened in the area in order to exploit local granite deposits, and Flossenbürg developed into a workers’ village.

At the same time, the region was discovered as a holiday destination. After the National Socialist seizure of power, the granite deposits and castle became the site’s key locational factors.

The quarry industry shaped social relations in the village and influenced the culture and self-perception of its inhabitants.

Flossenbürg remained a destination for day trippers. The border region increasingly drew nationalist and völkisch groups, which stylized the ruins as a bastion of resistance to the “Slavic peoples.”

The National Socialist state construction program created a boom in the demand for granite. As a result, quarry owners and workers welcomed the National Socialist seizure of power.

![]()

Flossenbürg stoneworkers on the castle hill, 1896

![]()

Hay harvest in Flossenbürg, ca. 1920

![]()

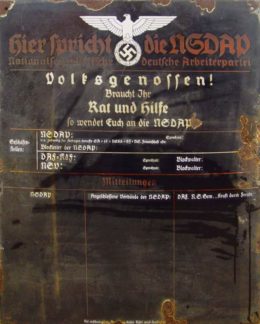

Nazi Party announcement board for its local chapters, 1933

The Founding of the Flossenbürg Camp (1938)

The Flossenbürg camp was established in May 1938 during the SS reorganization of the entire concentration camp system. In the new system, the purpose of the camps was no longer only to imprison and terrorize political opponents of the Nazi regime.

Rather, the SS now also aimed to profit from the exploitation of prisoner labor. Prisoners were put to work in SS-owned economic enterprises for the production of building materials. To this end, the SS founded new camps, and deported ever larger numbers of people to the camps.

The construction of new camps began in 1936-37 with the founding of the Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald camps. SS economic interests played an increasing role in the selection of new camp sites. The large granite deposits around Flossenbürg attracted the attention of the SS.

The decision on the Flossenbürg site was reached in March 1938. The first SS guards arrived in late April. On May 3, the first transport of 100 prisoners arrived at the construction site from the Dachau concentration camp. By the end of 1938, the initial intake of the camp had increased to 1,500 prisoners.

![]() View from the hill onto the future camp grounds, mid-1930s

View from the hill onto the future camp grounds, mid-1930s![]()

Postcard from Flossenbürg, 1938

![]()

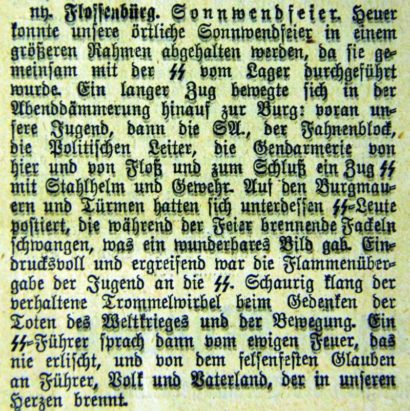

Article from the "Bayerische Ostmark" newspaper, June 23, 1939

On June 23, 1938, the first press release appeared that referred to the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp. In a short note, the author reports on the participation of the camp SS at the solstice celebration in Flossenbürg.

![]()

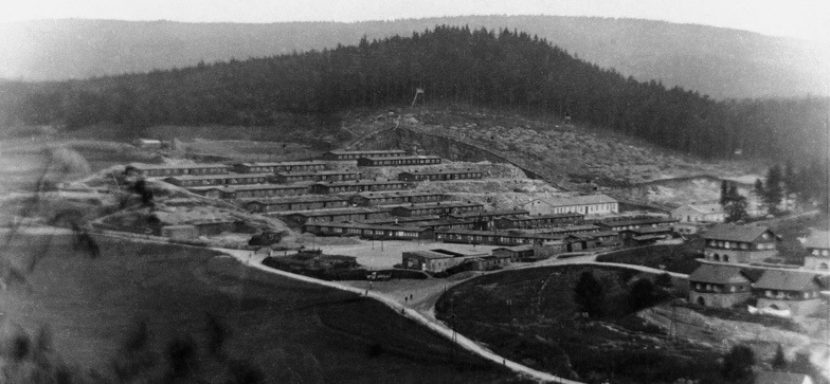

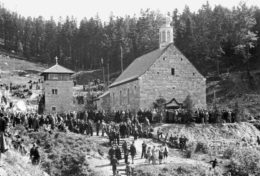

Flossenbürg concentration camp grounds, 1940

Camp Construction and Expansion (1938–1940)

The number of prisoners in the Flossenbürg concentration camp continued to rise. The arrival of new categories of prisoners fundamentally altered the composition of the prisoners’ forced community.

Two years after the camp’s founding, the main buildings of the camp were all complete. An SS company, the German Earth and Stone Works (DESt), mercilessly exploited the prisoners to excavate granite. Over 300 inmates had already perished since the founding of the camp.

The first inmates of the camp were Germans, victims of the arrests of so-called “criminals” and “asocials.”

In late 1938, the first political prisoners arrived. After the start of the war, Flossenbürg housed prisoners from across occupied Europe. The first Jewish prisoners arrived at the camp in 1940.

By this time the first phase of camp construction had been largely completed and the quarry was in full operation. The camp housed over 2,600 prisoners, and the death rate began to rise. To dispose of the bodies of the dead, the SS ordered the construction of a crematorium in the camp.

Survival and Death in the Camp (1938–1945)

Daily life in the concentration camp was dangerous and often deadly for the prisoners. Conditions were cruel and inhumane. Subjugated, humiliated, and exploited as forced labor, many prisoners died from mistreatment.

The SS established a system of violence and terror in the camp, and attempted to exploit the political, national, social and cultural differences among prisoners.

Between 1938 and 1945, approximately 84,000 men and 16,000 women from over thirty countries were imprisoned in the Flossenbürg camp and its subcamps.

All inmates were forced to wear prisoners’ garb bearing a number and colored triangle.

Living conditions deteriorated drastically over the course of the war. There was a steady rise in the number of accidents, illnesses and deaths. The ability to work increasingly determined a prisoner’s chance of survival. In late 1943, large transports began to arrive at Flossenbürg, overcrowding the main camp. Many prisoners were subsequently transported to subcamps. For most inmates, the decisive question became “How will I survive one more day?”

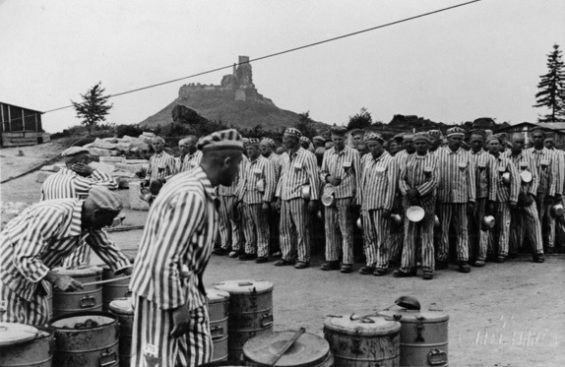

Meal call in the quarry, SS photo, 1942

The Prisoners of the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp

Work and Death in the Quarry (1938–1945)

Thousands of concentration camp inmates were forced to work in the quarry, owned by the German Earth and Stone Works (DESt). Inadequately clothed and lacking all safety precautions, the prisoners were forced, no matter the weather, to remove soil, blast granite blocks, push trolley wagons, and haul rocks. Accidents were daily and routine. Backbreaking labor, freezing cold, severe malnourishment, and random SS and Kapo violence led to the death of many prisoners.

A work day in the quarry lasted twelve hours, interrupted only by a single break when a thin soup was served. The SS forced prisoners to walk in circles for hours, hauling rocks.

Only a few prisoners survived these penal detachments. At the end of the work day, the prisoners carried the bodies of the dead back to the camp.

The camp quarry was the largest industrial operation at Flossenbürg. By mid-1939, approximately 850 camp inmates labored in the quarry daily; by 1942, the number had increased to nearly 2,000. DESt employed up to 60 civilian staff, administrators, stoneworkers, drivers and apprentices. Many of them had regular contact with the inmates.

The SS in Flossenbürg (1938–1945)

The administration and surveillance of concentration camps was one of the central duties of the SS (Schutzstaffel). SS members employed in the camps were all members of the Death’s Head Divisions (Totenkopfverbände). The SS conceived of itself as an ideological order and racial elite.

Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer SS, developed the SS into a complex organization, involved in matters ranging from settlement policies to “combating enemies” and systematically killing members of so-called “inferior races.” In addition, the SS ran its own business enterprises.

In the concentration camps, the Death’s Head Divisions were organized into the command staff and the guard units. Each camp was headed by a Kommandant. Along with his subordinate departments, the Kommandant determined the prisoners’ fates.

The SS staff were responsible for guarding the prisoners.

Approximately ninety SS members worked in the command staff at Flossenbürg. By spring 1940, the guard units had grown to a force of nearly 300. By 1945, with the construction of subcamps, the guard units expanded to approximately 2,500 men and 500 women. After the start of the war, many younger SS men were sent to the front. The SS leadership then engaged older men, air force soldiers, women, and foreign nationals for duty in the camps.

After the war, the majority of SS members received only light punishment for the crimes they committed at Flossenbürg.

Executions and Mass Murder (1941–1945)

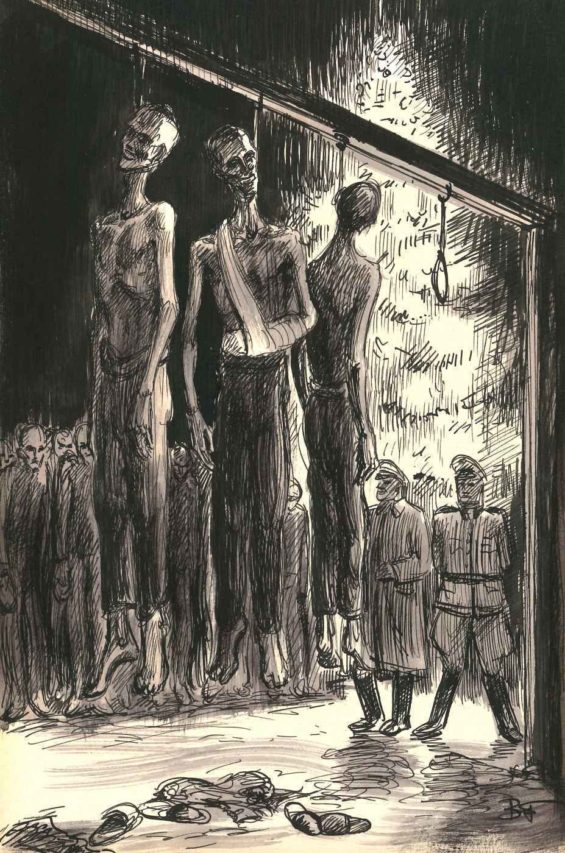

From the beginning, prisoners perished at the Flossenbürg concentration camp. They died of starvation, cold, and random violence. After escape attempts or alleged acts of sabotage, inmates were hanged on the roll-call square to serve as examples. In February 1941, the SS began mass killings of certain categories of prisoners.

Bruno Furch: Christmas Eve 1944 (Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance, Vienna)

Although the SS attempted to carry out the killings in secrecy, the executions did not go unnoticed. Inmates saw the SS execution commandos in the camp, and their fellow prisoners vanished without a trace.

Prisoner details removed the dead, and the crematorium commandos had to dispose of the victims’ remains. Prisoner-clerks were put to work crossing off names from camp lists.

In programmatic fashion, the SS murdered Polish concentration camp inmates, foreign forced laborers, Soviet prisoners of war, and the elderly, sick, and infirm. Shortly before the end of the war, many prisoners active in the resistance joined the victims. The SS in the Flossenbürg camp took part in at least 2,500 systematic executions.

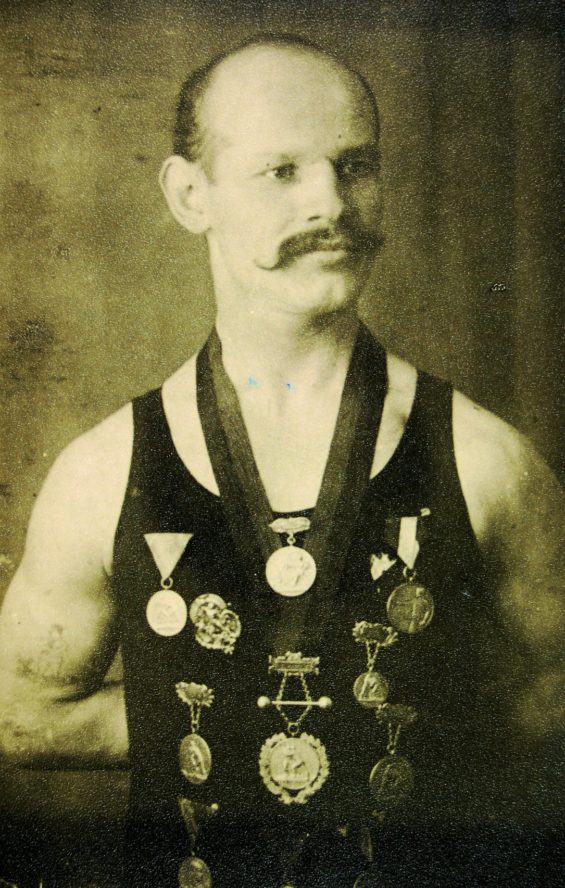

The multiple award-winning cyclist Eugen Plappert, ca. 1930

The fifty-five-year-old Eugen Plappert had been imprisoned in the Flossenbürg concentration camp since 1938. Due to his age and to a nervous condition, the SS transferred him and over 200 additional prisoners to Bernburg. Plappert and the other selected prisoners were told they were being brought to a country estate to recuperate. On May 12, 1942, Plappert was killed there by gassing.

The Flossenbürg Subcamps (1942–1945)

Beginning in 1942, the Flossenbürg concentration camp, like other main camps, became the epicenter of a widely dispersed auxiliary camp system. Its nearly 80 subcamps extended from Würzburg to Prague, and from Saxony to Lower Bavaria. Twenty-seven subcamps held female prisoners. Work conditions and chances of survival varied greatly among the subcamps.

The Flossenbürg command staff assigned prisoners to businesses and SS agencies, and was responsible for guarding the prisoners. It also collected the monthly payments for the prisoners’ forced labor. At first, a prisoner’s occupation determined his or her assignment to a specific subcamp. Toward the end of the war, the SS arbitrarily shifted prisoners between the main camp and the subcamps.

Civilian authorities and businesses participated in constructing most of the subcamps. In many cases, the local population was confronted for the first time with concentration camp inmates. Often prisoners of war and forced laborers provided assistance to camp inmates. On occasion, Germans also gave food to the inmates or secretly passed along letters from the inmates to their families. Heavy labor and hunger characterized everyday life in the subcamps. Many inmates attempted to escape, but seldom with success.

Economic Factors and Armaments Production (1943)

The Flossenbürg concentration camp quickly became a significant economic force in the region. Some businesses supplied goods to the camp, while others borrowed prisoners for a variety of tasks. After 1942, only key armaments suppliers were permitted to exploit prisoner labor. In early 1943, the Messerschmitt Works at Regensburg transferred a portion of its production to Flossenbürg.

Beginning in 1940, regional businesses, administrative agencies, and private individuals applied to the Flossenbürg headquarters for prisoners. The prisoners carried out agricultural work and manual labor under guard for limited periods.

By 1942, the German leadership began to prepare for a protracted war. In February 1942, the SS established the Economic and Administrative Main Office. This centralized office was harged with ensuring that prisoners would be allocated only to the armaments industry. Many companies transferred production to concentration camps. In 1943, Flossenbürg also became an armaments site. In the quarry grounds, prisoners worked on the production and assembly of the Me 109 fighter plane.

By the end of the war, over 5,000 prisoners worked for Messerschmitt. Quarry operations were largely suspended.

The Flossenbürg Camp in the Final Year of War (1944)

In mid-1944, the SS began to evacuate the concentration camps in occupied Europe. Massive prisoner transports thus began to arrive at Flossenbürg.

At this point, concentration camp prisoners were the final reserve labor force for the armaments industry. Conditions in the camp continued to deteriorate due to permanent overcrowding. At the end of 1943, over 3,300 prisoners were incarcerated at Flossenbürg; one year later, the number exceeded 8,000. On February 28, 1945, the Flossenbürg camp held 14,824 prisoners.

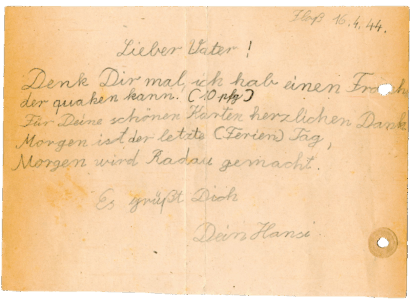

![]()

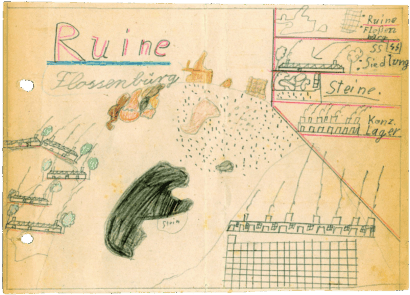

Letter from Hans Halboth with a sketch of the camp, April 16, 1944

![]()

The eight-year-old Hans fled with his mother from the Berlin bombings to relatives in Floß. While going for a walk to the Flossenbürg cemetery, he also saw the concentration camp. In a letter to his father, Hans drew what many later would refuse to acknowledge: the camp and the SS housing estate were as much an element of the local landscape as the castle ruins and the granite.

Due to the evacuation of the Auschwitz, Groß-Rosen and Plaszow concentration camps, thousands of Jewish prisoners were deported to Flossenbürg for the first time since 1942. A further 3,000 Poles arrived at Flossenbürg after the Warsaw uprising was crushed.

New arrivals to Flossenbürg were first confined to quarantine blocks. Each of these barracks housed up to 1,500 prisoners. Inmates assigned to work details worked for Messerschmitt in Flossenbürg or in one of the many newly erected subcamps. The SS moved anyone unable to work to the death barracks 22 and 23. In the winter of 1944, disease, starvation, and exhaustion resulted in a rapid increase in death rates. During the final year of the war, more inmates died than during any other phase.

![]()

The death train from Leitmeritz passing through Kralupy, photographed secretly by an unknown Czech photographer, April 29, 1945

Death Marches. Chaos. Liberation. (Frühjahr 1945)

The dissolution of the Flossenbürg concentration camp and subcamps began in early April 1945. Shortly before the end of the war, thousands of prisoners died of exhaustion on the death marches, or were shot or beaten to death. Many tried to escape.

On April 23, the US Army reached the Flossenbürg concentration camp, where they found 1,500 critically ill inmates. The majority of prisoners had departed on death marches. The last death march prisoners were finally liberated by Allied troops on May 8.

In addition to the thousands of prisoners who had just been evacuated from the Groß-Rosen and Buchenwald camps, the SS also removed “special prisoners” to Flossenbürg. Some of these special prisoners, including pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, were singled out for execution.

Before the SS evacuated the camp, it erased the traces of its murderous activities. Beginning in mid-April, the SS “evacuated” over 40,000 prisoners from the main camp and numerous subcamps to the south. On chaotic marches that lasted for many days and transports in open freight cars, the SS attempted to herd prisoners away from the approaching Allies. Some guards killed entire groups of prisoners. Others deserted their posts. In many areas, the dead were left behind. Many prisoners died of exhaustion and disease even after liberation.

“On the morning of the 23rd they were there with a jeep and a machine gun wich stuck out of the window and four soldiers. They were chewing gum, they were smoking, and tears ran down my cheaks. I didn't realize that I were crying. For me it was like having a nervous breakdown, because I had the feeling that I can go home now, that I survived and could go home.”

End of War

Liminal Situation of the Liberation (Early 1945)

Two weeks before the end of the Second World War, American units reached Flossenbürg. They found only about 1,500 prisoners left in the concentration camp. Most of the prisoners were sent on death marches throughout Bavaria.

Transition and New Order (1945–1950)

Immediately after the liberation, the allies established a new order. In many places, the victims of the concentration camps were given dignified burials. The prosecution of the perpetrators began. Polish DPs in the former Flossenbürg Concentration Camp erected one of the first memorials. While the survivors of the camp were coming to terms with the extent of the losses they suffered, the German population demanded to draw a line under the past.

![]()

Burial of prisoners in the town of Flossenbürg, U.S. Army Signal Corps, May 3, 1945

![]()

Entrance to the Polish DP-Camp at Flossenbürg, 1947

![]()

Unveiling of the memorial site, May 25, 1947

Final Line and Integration (1950–1958)

The first post-war decade in Germany is determined by the repression of recent history in favor of the integration of persons with a Nazi past. Former inmates attempt to forge a new start in their old homelands or elsewhere. The memory of the victims of the concentration camps amounts to nothing more than dignified burial grounds. This clears the way for the multiple reuses of the former concentration camp grounds.

![]()

Newly constructed cemetery for the victims of the concentration camp in Luhe, November 5, 1950

The concealed text on the commemorative stone reads: "Blessed are those who suffer persecution for the sake of righteousness."

Repression and Forgetting (1958–1970)

The cold war dominated not only politics in Germany and around the world – it also shaped the German conflict with the Nazi past. On the one hand, large criminal processes caused worldwide sensations. On the other hand, a lot was forgotten and repressed. In Flossenbürg, this is most evident in the construction of a housing development on the former camp grounds.

![]()

Demolition of the former detention yard, 1964

![]()

Commemoration for Wilhem Canaris in the former detention yard, Flossenbürg, April 9, 1965

![]()

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was also executed on the morning of April 9, 1945 in the detention yard

Selective Memory (1970–1980)

The political significance of the Nazi period declined. To be sure, the Ostpolitik of the federal government and the terrorism of the RAF were discussed with a view of the past. But the particular memory of the victims of National Socialism applied only to certain groups, such as the men of July 20, and was discussed only by a few protagonists. It was not until the end of the decade that interest in the Holocaust grew.

![]()

Commemoration of the French Association of Flossenbürg in the former Janowitz subcamp, Vrchotovy Janovice (ČSSR), 1980

Controversial Rediscovery (1980–1995)

The 1980's and 1990's were years marked by social awakenings and political upheavels. Despite historical turning points, such as the collapse of socialism and German unity, the Nazi past was a topical issue. In many places, interest in the darker chapters of local history grew. In Flossenbürg, the community neglected the undesired remnants of the former camp grounds.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Former entrance to the prisoner camp, watchtower and "Valley of Death," 1980's

Legacies (1995–2010)

Even 60 years after the Second World War, the Nazi past had an impact – whether it was about the new Holocaust memorial in Berlin, payments to former forced laborers or discussions about the alleged victim's role of the Germans. In Flossenbürg, 1995 started with the construction of a memorial site, something for which the survivors had passionately campaigned. It was only from this point that the "forgotten concentration camp" became distinguished as a European place of remembrance.

Discoveries on the former camp grounds, 2000–2010

![]()

Michal and Josef Salomonovic with the book of names, 2005

![]()

The "Children of Indersdorf": Mendel Tropper, Eric Hitter, Leslie Kleinman, Meir and Schmuel Reinstein, Dov Nasch, Avraham Leder and Martin Hecht with their photographs from 1945

![]()

Leon Weintraub at the permanent exhibit, 2010

What Remains?

Only with the institutional establishment of the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial, did the transformation of a cemetery into a museum, a place of remembrance and a place of learning begin. In 2015, the extensive redesign of the outdoor area was completed with the opening of an education center and the Museum Cafe. Two permanent exhibits provide information on the history of the concentration camp and its aftermath.